You May Be Surprised How Many Bornagain Christians Use Ashley Madison

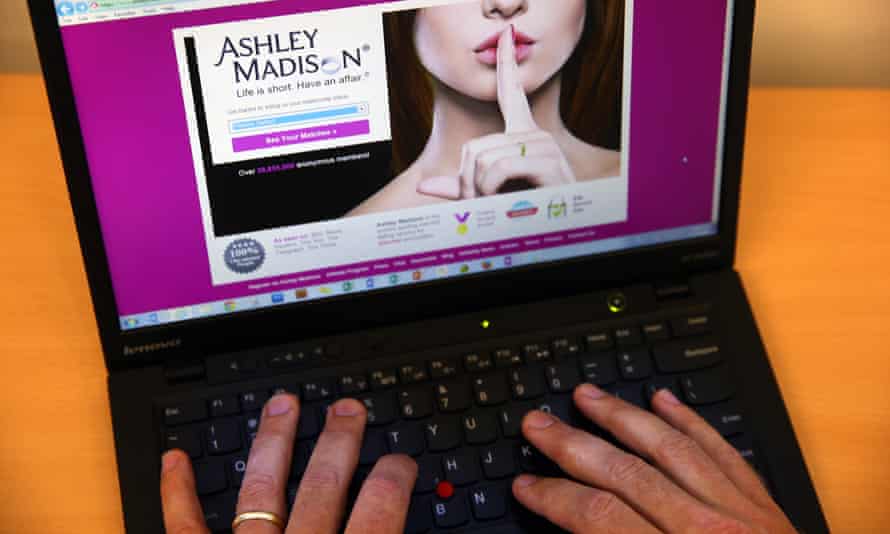

I t was 9 o'clock on a Sunday night terminal July when a journalist called Brian Krebs came upon the scoop of his life. The 42-yr-old was at home in Virginia at the time, and wearing pyjamas. For years Krebs had written a popular blog nearly internet security, analysing thefts of consumer data from big companies effectually the world, Tesco, Adobe, Domino's Pizza among them. Now Krebs, as his weekend came to an end, was existence tipped off about a more than sensational breach. An anonymous informant had emailed him a list of links, directing him to caches of information that had been stolen from servers at a Canadian house called Gorging Life Media (ALM). Krebs vaguely knew of ALM. For years it had run a notorious, widely publicised web service chosen Ashley Madison, a dating site founded in 2008 with the explicit intention of helping married people have affairs with each other. "Life is brusk. Accept an affair" was the slogan Ashley Madison used.

At the time Krebs received his tip-off, Ashley Madison claimed to take an international membership of 37.6 million, all of them assured that their use of this service would be "anonymous", "100% discreet". Only now Krebs was looking at the real names and the real credit-card numbers of Ashley Madison members. He was looking at street addresses and postcodes. Among documents in the leaked enshroud, Krebs institute a list of phone numbers for senior executives at ALM and Ashley Madison. He even found the personal mobile number of the CEO, a Canadian called Noel Biderman.

"How you lot doing?" Krebs asked Biderman when he dialled and got through – still not sure, until this moment, that he was on to a legitimate story.

Biderman said: "You can probably guess."

And then the CEO of Ashley Madison began the slow, careful piece of work of begging Krebs non to publish anything virtually the most appallingly intimate net leak of the modern age.

Only a few hours subsequently, in the west of England, a contentedly married man nosotros'll phone call Michael woke upwards and went through his usual Monday-morning routine. Coffee. Email. A skim of the news online. Already Krebs'due south story about a hack of servers at Ashley Madison had been picked up past prominent media agencies. The story was a lead detail on every news page Michael browsed. Adultery site hacked, he read; a group calling itself the Impact Team claiming responsibility and threatening to release a total database of Ashley Madison customers, present and past, inside a calendar month. More than 30 million people in more than 40 countries affected.

Though in the days to come the number of active users of Ashley Madison's service would be disputed – was that figure of 37.vi million for real? – Michael could say for certain there were many authentic adulterers who used the site because he was one of them. "I'd taken some elementary precautions," Michael told me recently, explaining that he'd registered on Ashley Madison with a surreptitious email address and chosen a username by which he couldn't be personally identified. He had uploaded a photo. He was experienced plenty with adultery websites – Ashley Madison and a British equivalent called Illicit Encounters – to know that "if you don't put a photograph upwardly you won't go many responses". Merely the picture show he chose was minor and he was wearing sunglasses in it. "Deniable," Michael said.

Whenever he visited the site he was careful. If he wanted to log on to Ashley Madison to speak to women he would only do so on a piece of work laptop he kept in his office at home. Michael had six internet browsers installed on the laptop, and one of these browsers could only be loaded via external hard drive – this was the browser he used to conform affairs. Then Michael was "irritated and surprised" to realise, that Monday morning, that his elaborate precautions had been pointless. He tried to work out means in which he would exist exposed if the hackers went through with their threat to release Ashley Madison's customer database.

Subscriptions to the site were arranged so that women could employ the service for free while men paid a monthly fee – this, in theory, to encourage an even balance in its membership. Michael had joined Ashley Madison subsequently seeing it written about in a newspaper. He recalled getting a deal as a new signee and being charged something like £20 for his beginning month. He paid using his credit card. The profile name and email address he'd chosen were no threat, the photo deniable – "but your credit carte," Michael realised, "is your credit card." At this time there would have been a lot of men (even conservative estimates put the number of paid- up Ashley Madison subscribers at the time well into the millions) thinking: your credit card is your credit card.

Michael followed it all from his abode estimator as the story evolved, through July and into August, into an enormous, consistently foreign, consistently ghastly global calamity.

On eighteen August, Ashley Madison'south entire customer database was indeed put online. In the subsequent panic, rewards for information most the hackers were offered. Police in Toronto (the city where ALM was based) vowed to observe the culprits. Meanwhile politicians, priests, military members, civil servants, celebrities – these and hundreds of other public figures were found among the listed membership. Millions more, formerly anonymous, suddenly had their private details sprayed out on to the internet. It varied according to an individual's caution when signing up to the site, and to their luck, and to their gender (the men in general more exposed considering of Ashley Madison'due south requirement they pay by credit card), merely subsequently the leak some people establish they could be identified not only past their names and their addresses just also by their height, their weight, even their erotic preferences.

Moral crusaders, operating with impunity, began to shame and squeeze the exposed. In Alabama editors at a paper decided to print in its pages all the names of people from the region who appeared on Ashley Madison's database. Later on some high-profile resignations all around North America, people wondered if at that place might not exist a run a risk of more tragic repercussions. Brian Krebs, with some prescience, wrote a web log advising sensitivity: "There'south a very real adventure that people are going to overreact," he wrote. "I wouldn't be surprised if we saw people taking their lives because of this."

A small number of suicides were reported, a priest in Louisiana amidst them. Speaking to the media after his death, the priest's wife said he'd found out his name was among those on the list before he killed himself. She said she would take forgiven her hubby, and that God would have too. "God'due south grace in the midst of shame is the center of the story for us, non the hack. My husband knew that grace, but somehow forgot that it was his when he took his own life."

During the early weeks of the crunch ALM, the company behind Ashley Madison, stopped responding in any sort of acceptable way to calls and emails from its terrified customers. Endless marriages were at risk, people teetered on appalling decisions, and meanwhile ALM put out brisk press releases, one announcing the difference of CEO Noel Biderman. It made superficial adjustments to the front of its website, at some indicate deciding to remove the graphic that described Ashley Madison as "100% unimposing".

And so the masses sent spinning by the leak could not turn to ALM for advice. Almost could not easily turn to their partners. Someone had to fill this enormous absence, hear grievances. Troy Chase, a mild-mannered technology consultant from Sydney, had not expected it would be him.

As the crisis developed he plant that dozens and and so hundreds of people, caught upwards in the event, were looking to him for help and for counsel. Hunt, who is in his tardily 30s, explained what happened. His expertise is internet security; he teaches courses in it. As a side project, since 2013, he has run a gratis web service, HaveIBeenPwned.com, that allows concerned citizens of the internet to enter their email address, become through a simple procedure of verification, and then learn whether their personal information has ever been stolen or otherwise exposed in a information breach. When hackers pinched information from servers at Tesco, at Adobe, at Domino's Pizza, Chase trawled through the data that leaked and updated his site and so that people could apace find out if they were affected. After the Ashley Madison leak he did the aforementioned.

Only this time, Hunt recalled, desperate and difficult and extremely personal messages began arriving in his inbox almost immediately. By and large it was men who emailed – paying customers of Ashley Madison who mistakenly believed that Chase, having sifted through the leaked data, might exist able to help them. Could he somehow scrub their credit cards from the list? Chase described the tone of these emails as fearful, illogical, "emotionally distraught". About a hundred emails a twenty-four hours arrived in that early flow, Hunt recalls. Considered together they grade a bleak and fascinating historical document: a clear view into the hivemind of those caught up in the leak, caught out.

People confessed to Chase their reasons for subscribing to Ashley Madison in the start place: "I joined Ashley Madison i night bored, honestly… Curiosity… Drunken evening…" They volunteered to him what they'd done, or nearly done, or hadn't washed at all. They described what it was like to learn near the leak: "The worst dark of my life… Sheer fright… Sick and foolish… I can't sleep or eat, and on superlative of that I am trying to hibernate that something is incorrect from my married woman…" They pleaded with Chase (who could practice nothing for them). They apologised to him (a stranger). They wondered if they should admit everything to the people who mattered to them. And they wondered what that might cost. "Tell your wife and kids you beloved them this evening," said one email. "I shall do the same, equally I actually don't know if I will take many more chances to do so."

Some of those who got in touch, Hunt told me, mentioned suicide. He didn't know what to do. He was a computer consultant. He sent back the numbers of telephone helplines.

Who was backside the hack? Who was the Bear on Team that claimed responsibleness?

Troy Hunt ofttimes wondered most that. He knew a lot virtually data theft at large corporations, what it tended to look like. Chase idea this episode seemed "out of graphic symbol" with many such hacks he'd seen. The theft of such a large corporeality of data usually suggested to Hunt that somebody employed by the company (or someone who had physical access to its servers) was the culprit. But then, he reasoned, the subsequent leaks had been and so careful, so deliberate. "They came out and said: 'This is what we're going to practice.' So radio silence. And then a month after: 'Here'south all the data.'" It was sinister, Hunt thought, militaristic even.

Then there was the jarring strand of moralising in the messages the Touch Team did put out. "Learn your lesson and brand amends" was the group'south advice to any of Ashley Madison's users left in pieces by their work. Not the obvious behaviour, Hunt suggested, of a revenge-minded staffer who only wanted to injure his or her employer.

Brian Krebs made efforts to empathise the hackers, too. He'd never been able to effigy out who first tipped him off, just he wondered at 1 point if he'd establish a promising lead. In a detailed weblog, published in late August, Krebs followed a trail of clues to a Twitter user who seemed to have suspicious early on knowledge of the leak. "I wasn't saying they did it," Krebs told me, "I was but maxim that maybe this was [a line of investigation] that deserved more attention." He didn't know if law forces investigating the case ever followed up on his pb. The Toronto force, to appointment, has appear no arrests. (When I asked, recently, if there had been whatever developments their press section did non answer.)

Krebs told me: "Whoever's responsible – no doubt they know that there are now lots of people wanting to put a bullet in their head. If it were me, if I was going to exercise something similar this, I would brand pretty darn sure that nobody could trace information technology back to me." At to the lowest degree in public, the Impact Team has not been heard from once more.

What motivated the hackers, then? In the initial bribe note the Affect Team suggested that unseemly business organisation practices at ALM – for example a policy of charging users to delete their accounts on Ashley Madison and so continuing to store departing users' personal information on internal servers – had provoked the hackers' ire and justified its attack. Merely the mass release of private data, to make a point about the maltreatment of private data, cannot accept seemed to anyone a very coherent reason for doing all this.

To endeavour to better understand the thinking of the Affect Team I spoke to hackers who said they were not involved with the Ashley Madison attack only had kept a shut center on information technology. The general supposition, in this customs, seemed to be that attacking a firm such every bit Avid Life Media (a scrap shouty, a bit sleazy) was fair game. Few felt the mass release of millions of people'southward personal information – they chosen it "doxing" – was ideal hacker etiquette though. "Non sure I would have doxed 20 1000000 people at the same fourth dimension," 1 said. Even so they felt the saga would teach the globe a useful lesson. "Anyone doing annihilation online," I was told, "should assume it isn't secure."

1 hacker I spoke to said he'd spent hours and hours digging through the Ashley Madison data after the leak, going out of his way to draw attention to his nigh salacious findings. Speaking to me by email and in individual chatrooms, he asked that I call him AMLolz, for "Ashley Madison laughs". We discussed some of the findings he'd fabricated and after publicised, through an AMLolz Twitter feed and an AMLolz website. He noted with some pride that in i of his deep searches he'd come up beyond emails that suggested members of Ashley Madison's staff were themselves having extramarital affairs. He had posted screenshots of incriminating personal letters, and several magazines and newspapers had picked up on his findings and run stories.

AMLolz might not have been involved in the Ashley Madison hack, just he was certainly involved in giving information technology an impactful afterlife. I asked him what motivated him. Disapproval? Revenge? "Because it was very humorous," he said somewhen. "And very interesting. No mission argument, simply looking for lols."

AMLolz used the term "peripheral damage" more than than one time in chat, neatly encompassing, in those words, all the sleepless unfaithful and their tortured other halves, the newly unemployed, the dead, their doubly grieving widows. I asked AMLolz what he would tell one of these "peripherally damaged" if he were to meet them in person.

He replied: "Information technology would depend what they had to say to me first. [Smiley face.] That being said, something along the lines of: 'Own your deportment. Don't lie to yourself, or anyone else…' It's not good. [Thoughtful face.]"

In the west of England, Michael could hardly disagree with this. Fifty-fifty as he sat in his home office, reading the developing news about Ashley Madison and wondering if his wife was doing the same, he was well aware of his own culpability. He didn't think he had anyone else to blame just himself. Who was he really going to blame? Ashley Madison? "I recall it would probably exist a piffling naive of me to look loftier standards from a company that was promoting itself as a meeting point for people looking for cheating affairs. It'due south a scrap like borrowing coin off your drug dealer and expecting him to pay it dorsum." Michael but accepted what was going on and watched, with a numb fascination, as the crunch rolled on.

In August, the private detective manufacture reported, cheerfully, an uptick in business. Lawyers steered high-publicity legal actions against Ashley Madison – at least iii plaintiffs in America wanted to sue – as well equally seeing through quieter divorce claims. In Australia a DJ decided to tell a woman live on air that her husband was on the database. Members and former members began to be sent anonymous extortion letters. Michael received several. Pay u.s. in seven days, he was threatened in one email, "or y'all know what volition happen… You tin can inform authorities but they tin can't assistance you lot. We are porfessionals [sic]." Michael was unnerved by the emails simply ignored them. The earth, in these modest increments, got shabbier.

Like Troy Hunt in Australia, Kristen Brown, in California, institute herself operating as a sort of on-the-become counsellor during these foreign months. For Brown, a 29-year-onetime journalist, it began when she started interviewing victims of the Ashley Madison leak for the website Fusion.net. Interviewees kept wanting to talk, though, long after she'd published – a lot of these people, Brown guessed, left without anyone else they could speak to bluntly. "I was basically operation as a therapist for them. They were crushed by what happened." Brown guessed she'd spoken to about 200 of those affected by the hack over the past six months.

To an unusual caste, Chocolate-brown thought, a tone of moral judgment skewed the commentary and discussion around the Ashley Madison matter. "It's a gut reaction, to laissez passer a moral judgement," she said. "Because nobody likes the idea of being cheated on themselves. Yous don't want to find your ain partner on Ashley Madison. Just spending hours and hours on the telephone with these people, it became so clear to me how frigging complicated relationships are."

Dark-brown connected: "We all have this idea of the site every bit completely salacious, correct? Cheating men cheating on their unassuming wives. And I did speak to those men. But so I spoke to others who'd, say, been with their married woman since they were 19 – they loved their wives but there were problems, there were kids, they'd stopped sleeping together. They had practiced partnerships, their lives worked, they didn't want to upend everything. They just weren't fulfilled or satisfied romantically. Some people were on the site with the permission of their spouses. I talked to i woman who was afraid to leave her husband, and beingness on Ashley Madison was her way of working out what to do. Some people I spoke to were unmarried and didn't want attachment and using Ashley Madison was but a way. People's reasons were complex. They were real."

This, more or less, had always been Michael'south reasoning for cheating. His situation was complex, and real. He told me he had been unfaithful to his wife "from later on we outset got married", conducting a string of one-off or months- or years-long diplomacy for nearly 30 years. "As life partners, my wife and I fit really well. We are very, very practiced friends – that describes united states. But I know at that place'due south a missing dimension to our relationship."

Ashley Madison was a way to endeavor to account for that missing dimension.

And non always, said Michael, a particularly satisfying manner. He wasn't fifty-fifty sure that every woman he spoke to during his fourth dimension on the site was 18-carat. Sometimes, when conversation had a flavour of "classic soft porn", he said, he wondered if his correspondents were employees of the company, reading from scripts. (The likely truth, as suggested past internal documentation made available in the leak, was stranger still. Coders at Ashley Madison had created a network of faux, flirtatious chatbots to converse with men like Michael, teasing them into maintaining their subscriptions on the site. It was for this reason that commentators began to doubt whether Ashley Madison had equally many subscribers every bit information technology advertised; Avid Life Media, e'er since the leak, has always claimed to have a healthy and fifty-fifty growing userbase.)

Michael had met someone real through Ashley Madison. Similar him she was in a stable companionable wedlock, only ane that lacked a certain dimension. She lived in the northward of England. She had children. She and Michael shared tastes in books and spoke a lot on the phone. Sometimes they discussed their partners and their corresponding marriages, other times they steered from the subject. There was a sexual element to the matter, Michael said, merely they never slept together. Information technology was a relationship that was precious to him.

"If you're going to conversation a adult female upwardly in a bar, or at a work conference, or wherever," Michael told me, "and so: 'Hello, I'thou married' is not a practiced opening line. Whereas if you're going on to a website like Ashley Madison – they know. It'southward a scrap ridiculous to talk about honesty in terms of these relationships. Only they actually first with honesty. Because you're not pretending to be something you lot're not."

Ashley Madison was a way of having a "safe matter", he said. Rubber in the sense that he didn't think it likely he'd be constitute out past his married woman (he had his special browser, his secret email accost). As well rubber in the sense that he didn't call back anyone would get hurt.Since the leak Michael had not used Ashley Madison again nor spoken to the adult female in the north. His wife, as of February 2016, had not found out most his diplomacy.

The hack of Ashley Madison was historic – the first leak of the online era to expose to mass view non passwords, not pictures, not diplomatic gossip, not military secrets, merely something weirder, deeper, less tangible. This was a leak of desires.

"I recollect that history'southward probably littered with examples of madams whose little black book went walking, you know what I mean?" said Brian Krebs. "But this was massive, en masse, on the internet. Who knows? Perchance nosotros demand privacy disasters like this to assist us wake up."

Kristen Brown thought it was important to accept away a different instruction from the saga. That spousal relationship is non ane thing, and that the millions of users of Ashley Madison very probable had millions of different reasons for existence on at that place. "At that place's a vibe between 2 people that can't be quantified. How to say what the right path is for any ane pair? Relationships are fucking weird. And they get weirder the longer they go on."

In London recently I met with Troy Hunt. He'd flown in from Australia to teach a corporate course on cyberspace security. Nosotros had lunch between morn and afternoon sessions in his classroom in Canary Wharf. While we ate Hunt showed me his phone – another email had just come in from someone requesting his help. 6 months had gone by since the leak; the menstruum of desperate letters had slowed but not stopped.

Chase responded to this electronic mail the way he always did now, sending dorsum a prewritten response that included a listing of answers to frequently asked questions about the hack. Also that listing of hotline numbers.

When nosotros'd finished eating his teaching resumed. Two dozen people filed into the room with their laptops and sabbatum quietly while Chase lectured them near cyber security. He'd worked a contemporary lesson into his voice communication, and projecting an image of a now-infamous website on to a screen behind him, he said to the class: "Put up your hand if any of you accept an account with Ashley Madison."

A nervous laugh went around the room. Nobody put up their hand.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/feb/28/what-happened-after-ashley-madison-was-hacked

0 Response to "You May Be Surprised How Many Bornagain Christians Use Ashley Madison"

Postar um comentário